Every December 31st, on New Year’s Eve, tradition makes time stand still in thousands of homes and, with great expectation, silence is made to hear the metallic lament of bells that mark the birth of a new year that is beginning and of a new life. The desired moment has arrived but, before you can toast and embrace each other, you must take the twelve grapes with the sound of each bell, to have 12 months of good luck and prosperity.

Have we ever wondered how those grapes are grown before they reach our table? Well, that’s what we’re going to try to explain in this Cultinews.

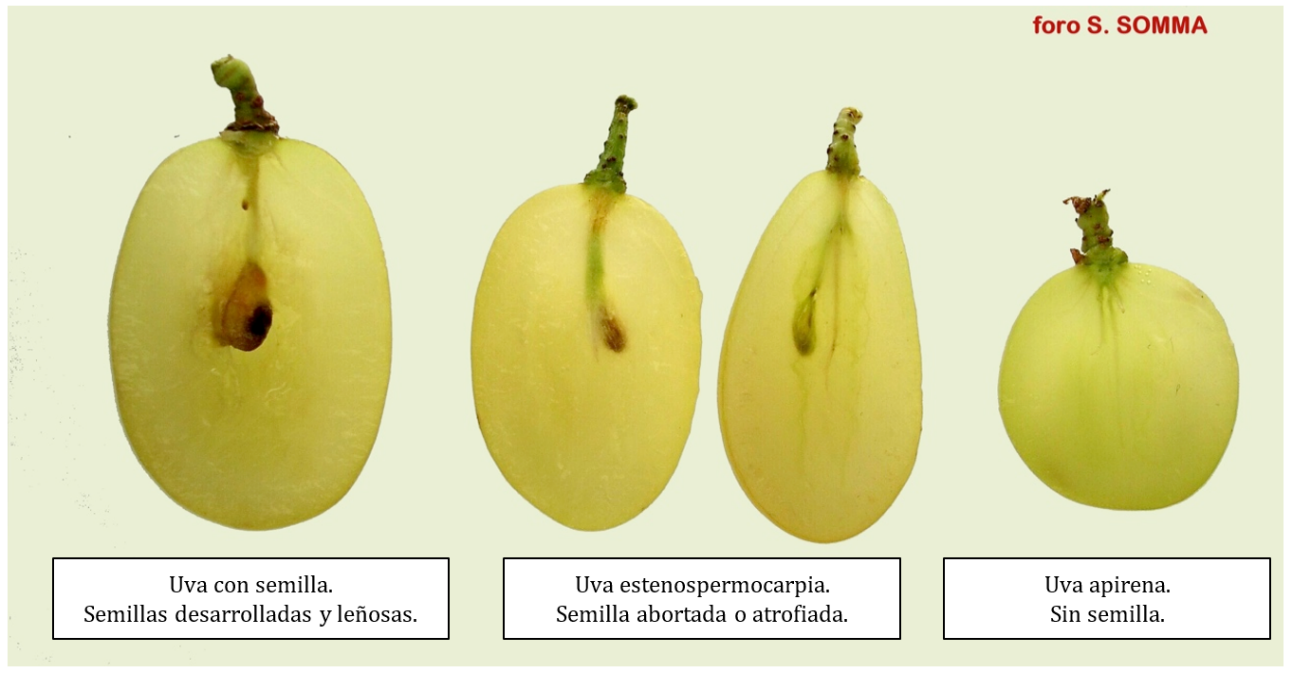

The cultivation of table grapes in Spain is mainly concentrated in the Levant, with the most productive provinces being Alicante, Murcia and Almeria. The trend in recent years, is that the demand for varieties apirenas (seedless) is increasing compared to traditional varieties.

Like any other crop, table grapes require a series of techniques and nutritional needs to be able to offer a sufficient and quality harvest, although it is true that cultivation techniques demand a large number of days’ work due to the difficulty of mechanisation.

One of the best techniques for keeping the grapes in the best possible condition until New Year’s Eve is, without doubt, the bagging of the bunch. This means that there is little or no need to apply phytosanitary products as the bunches are protected from unfavourable weather conditions as well as from pests and diseases, making it interesting to grow this crop in an ecological way.

To grow table grapes organically, it is recommended:

- Organic matter contribution, which will end up becoming highly stable humified material. The basis of organic farming is to maintain a stable, living, nutrient-rich soil.

- If the decomposition of these materials is slow, organic amendments must be used in the early stages of cultivation to provide the soil with the decomposed material required at that time.

- Avoid turning over ground horizons, making fewer passes and less deep. Sub-soiling may be a recommended option.

- Improve the quality of the soil with green manure and crop association.

- With mulch techniques we manage to maintain the porosity of the soil in its most superficial horizon.

- Use hedges and windbreak vegetation on the plot boundaries for crop protection.

- If the soil is affected by pests and diseases, solarization may be a method to consider.

The choice of the variety and the rootstock means the success or failure of the cultivation of the grape since once the vines are established, it is not something that can be corrected except by eliminating the existing ones and putting in new vines. It is vital to make a good selection of the variety, betting on those that the market demands the most. However, there is a wide range of possibilities at present. On the other hand, it is very important to know the agronomic characteristics and the potential of the different varieties in order to make our choice, since not all of them are adapted to each cultivation area, taking into account that we are going to be influenced by the following variables: climate, altitude, orientation, production objectives and final recipients of the product, that is to say, what type of market and customers we are going to dedicate ourselves to. For the choice of the rootstock or rootstock, obviously the factor that will influence most is the type of soil. It should be borne in mind that the compatibility between variety and rootstock plays as much, if not more, a role than the qualities of each individual part. We can have the rootstock best adapted to our soil and the variety we think is best for our purposes, but if the compatibility between the two is not good, we will not obtain the expected results.

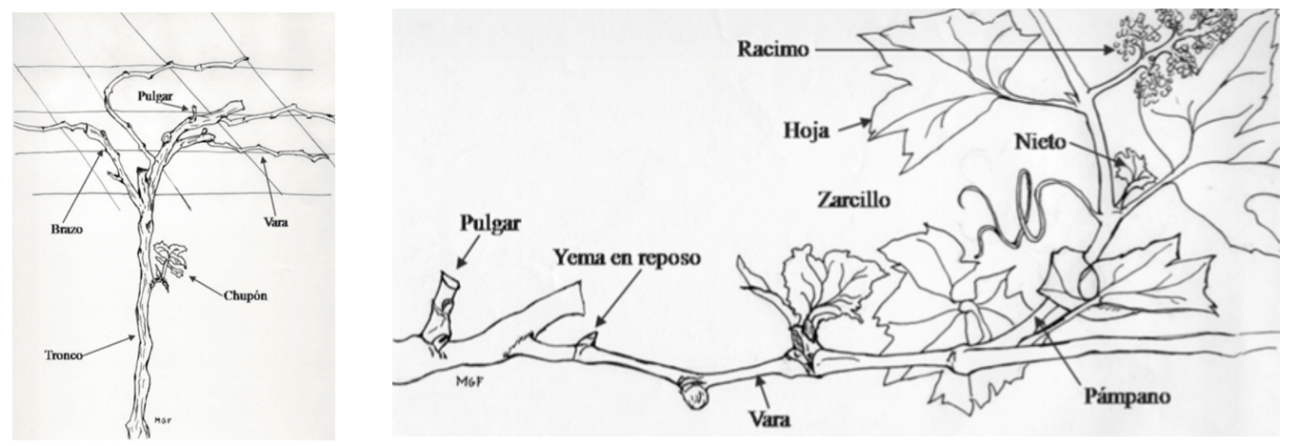

The conduction system in the table grape is also a determining factor in the type of grape and the quality that will be obtained during the life of the vineyard. There are several conduction systems that provide a very good quality of grapes. The most widespread is the vine training, although there are other possibilities such as high trellis training or “Y” training.

The vine arbour is made up of a horizontal wire mesh located at a height of about 2 m, and held in place by different posts (corner posts, props and right feet). The vine is driven forming a straight trunk with four main arms carrying the rods with the bunches. Generally the vine reaches full production in the fourth year after planting. It is becoming increasingly common to use a mesh structure, which is placed on the trellis forming a chapel over each line of cultivation. It can also be covered with a plastic sheet in order to advance or delay the harvest.

Fruit pruning is a dry pruning, which is carried out in winter with the vine at rest. Its main objective is to achieve a production in quantity and quality that remains constant over time. To this end, a balance must be ensured between the vegetative growth (shoots and leaves) and the reproductive phase (harvest). In addition, the pruning must maintain the size and shape of the vine obtained with the formation pruning, according to the plantation framework assigned. After the pruning, once the needs of cold have been covered and with the arrival of more benign temperatures, the buds, leaves and bunches are budded and grow. After a certain time we will be able to check the real percentage of sprouting and the real fertility of the current year and we can and must make the necessary adjustments to improve the productivity and quality of the harvest.

The tasks that are carried out after the buds have sprouted during vegetative growth are called green operations, whose aim is to maintain the balance between the vegetative and reproductive growth of the plant after winter pruning and to improve the productivity and quality of the harvest. Among the most important green operations we have:

- Flashing or flashing. The developing vines initially compete with each other for the reserves. Early elimination of those that will not be useful as producers or future shippers will improve the development of those that remain.

- Tied up. When the union of the base of the trunk to the branch has hardened, the branches are regularly guided and distributed on the grid, tying them to the wire.

- Cluster cutter. Together with the previous operation, the bunches are slid (wire from the grating and tendrils) and taken down to ensure that they develop properly and to facilitate the operations to be carried out later.

- It consists of the removal of the end of the growing shoots, which includes the apex and some leaves still growing. This operation is recommended for very vigorous varieties with setting problems and varieties sensitive to drop or in fresh and rainy springs, in order to improve the setting and the appearance and size of the bunches.

- It consists of removing some leaves in the area of the bunch in order to improve aeration and avoid diseases, as well as to increase the effectiveness of phytosanitary treatments.

- Sometimes together with leaf stripping the grandchildren are removed from the cluster area with the same aim, to improve ventilation and facilitate operations on the cluster.

- Cluster thinning. This consists of removing entire bunches of grapes in order to increase the quality of the fruit. Reducing the number of bunches increases the leaf/bunch ratio (number of leaves per bunch) so that these will receive more photoassimilated.

To achieve commercial quality in apirena varieties (seedless), with loose bunches, large and well shaped berries, specific cultivation techniques are required, such as the application of gibberellic acid, ringing and bunch pruning, which are not usually practiced in traditional seeded varieties.

In apirena varieties, the synthesis of gibberellins and the accumulation of sugars is lower. The exogenous application of gibberellins (gibberellic acid) favours the fall of fruits and the development of berries (less fruits, bigger berries). Not all varieties respond equally to treatment with gibberellins, some even do not tolerate it. The effects depend on the moment they are applied and the doses given.

The ring incision or ringing consists of the removal of a ring of bark and Liberian vessels (phloem), with the aim of interrupting for a short period of time (no more than 20 days) the flow of sap and accumulating sugars in the parts of the plant located above the incision, mainly bunches, to encourage their development.

Bunch pruning consists of removing parts of the bunch with the aim of improving the appearance, shape and form of the bunch, reducing its compactness and homogenizing the size and distribution of the berries. Normally, bunch pruning consists of eliminating the lower third and removing or trimming the wings or shoulders, así́ like some branches, until a well-formed bunch is left, with the appropriate number of berries.

Ripening can be defined as the set of changes in appearance and internal composition that occur in the bunches at the end of their growth and that cause the grapes to reach the texture, color, aroma and flavor characteristic of each variety, making them suitable for consumption.

Having reached this point, and here comes perhaps the most widely used technique to obtain a late, quality, sweet and uniformly coloured grape, we will talk about bagging, already mentioned at the beginning of this Cultinews. The technique literally consists of bagging and covering the growing bunch with a saturated cellulose paper. The paper is tied to the stem of the bunch and left open at the bottom, leaving the bunch covered and protected from the shoulders to its apical part. This bagging is left until the harvest providing numerous advantages:

- We delay the maturation. This is important if we want the grapes to arrive in the best condition on New Year’s Eve.

- We get a smooth and even color.

- We protect the cluster from insect and bird attacks, while avoiding certain

- We protect the bunch from direct sunlight and adverse weather conditions until the time of harvest.

- We also protect the bunch from the conditions in harvest and transport.

The table grapes are harvested with scissors by cutting the bunches from the stem, making several passes as not all bunches ripen at once, and placing them on trays or in boxes. Afterwards, the bunches are cleaned by removing the damaged or abnormal berries and packed. The labour requirements are quite high as the fruit is very delicate.

As far as nutritional needs are concerned, in Cultifort we can offer different options to produce quality table grapes, with complete formulations and guaranteed richness, zero residue and with alternatives for ecological production.

Finally, we wanted to count on Tobias Cantó Jover, Head of Production of the Santa María Magdalena Cooperative in Novelda (Alicante), who we asked about the challenges facing the sector. Here we leave you his answer or opinion:

The table grape, like the world economy, is living through turbulent times of adaptation and regeneration. The current situation means that table grape growers must invest in new types of management structures and new production varieties to offer products that are innovative and adaptable to the needs of consumers. Fresh products meet all these requirements, because they are healthy, convenient and of high quality.

The new types of structures go hand in hand with the new types of varieties or clones of table grapes, whose handling or cultivation is carried out under certain conditions that are only provided by these new structures, where the reproductive organs of the vine are arranged in a distributed and uniform manner along the horizontal space of distribution of the plant’s leaf system, since the use of new cultivation techniques, such as fattening and colour treatments, require a homogeneous distribution of leaf applications, in order for these to be effective or positive.

It is also true that this adaptation is the result of a greater economic investment than has hitherto been the case in the sector, since the possibility of planting new varieties requires the obtention of a license or planting right granted by the breeder of that variety, which requires the payment of an area fee and a fee for licensed plant material. In addition, the structures required for cultivation entail a higher cost due to the elements used in their construction, which mean that where wooden posts are nailed to the ground, they are replaced by aluminium structures and covered with anti-hail netting, in order to guarantee a quality and quantity harvest, since where the bagging technique is used, it must now be protected in other ways (anti-hail netting).

Another point to take into account in relation to the costs of this type of structure is that concerning agricultural insurance, which has helped the farmer so much in the past. The increase in the cost of these contracts due to the percentage increase by ENESA and the withdrawal of regional subsidies means that the diversion of these funds used to contract farmers to the new structures that carry out the agricultural insurance task must be taken into account.