The avocado (Persea americana Mill) is a fruit tree of Mexican origin of the family of the Laureaceas, introduced in Spain between the 17th and 18th centuries, although it was not until the middle of the 19th century that its cultivation was developed at a productive level.

At present, Spain is the only European producer and exporter of this exotic fruit, acting as a gateway to the rest of Europe, although there is also production in Portugal, in the Algarve, and testimonial plantations in Sicily and Crete.

The particular weather conditions required for avocado to survive make its cultivation limited to very specific places in the national territory. So much so, that the coastal areas of Malaga and Granada are the ones that concentrate 90% of the production of our country, with approximately 10,000 hectares (7,000 in Malaga and 3,000 in Granada) and a production ranging between 50 and 60,000 tons. The subtropical microclimate of these two provinces is ideal for harvesting this fruit, which takes place between November and May. Although the lack of water hinders the expansion of the avocado crop in Malaga, the price of the fruit and the increase in demand in markets such as Europe, which is its main production destination, do not cease to act as sources of attraction. Farmers in provinces such as Cadiz and Huelva have begun to invest in this crop and in communities such as Valencia it has not stopped expanding for years.

The total surface area in Spain, including the Canary Islands (around 1,500 hectares) is around 14,000 hectares with considerable growth, as we have just mentioned, in Cadiz, Huelva and the Valencian Community.

For all this, we have a guest of honour who will answer several questions related to this crop and more specifically, about the care it needs in its first years of planting. His name is Iñaki Hormaza Urroz, research professor and head of the Department of Subtropical Fruit Growing at the Institute of Subtropical and Mediterranean Horticulture (IHSM) “La Mayora”, located in the town of Algarrobo (Malaga).

Iñaki Hormaza holds a degree in Biology from the University of Navarra, Pamplona, in 1988, a diploma in Plant Breeding from the Mediterranean Agronomic Institute of Zaragoza (IAMZ), in 1989, and a PhD in Plant Biology from the University of California, Davis, in 1994.

In 2000, he obtained a position as a senior scientist at the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) and began working at the IHSM “La Mayora” in Malaga. Since 2003, he has been in charge of the Department of Subtropical Fruit Growing at this Institute and, since 2007, he has been a Research Professor at the CSIC. During his scientific career he has been involved in numerous national and international research projects focused on the study of genetic diversity, the characterization and conservation of germplasm and studies of reproductive biology in subtropical and temperate fruit trees.

Since joining the IHSM “La Mayora”, he has directed more than 40 regional, national and international research projects, 30 research contracts with the private sector and has collaborated on numerous additional projects. He has published nearly 200 scientific-technical articles, more than 100 of them in journals of impact and presented more than 130 communications to scientific conferences. He has been invited as a speaker by public and private entities in many countries. He has directed 16 doctoral theses.

He is currently the coordinator of the Latin American Native Fruit Trees Network financed by CYTED, where 55 researchers from 17 organizations belonging to 11 Latin American countries participate.

From Cultifort we want to thank him for accepting our invitation and we hope to be able to count on him in other occasions. THANK YOU VERY MUCH!

- I would like to deal mainly with the subject of new plantations, as a “guide to succeeding in an avocado plantation”, so I will start with the most essential. What soil-climatic requirements must be taken into account before carrying out a plantation? And preparation of the soil?

The main requirements have to do with the origin of the species in Central America and we can focus on temperature, rain and soil. In the avocado there are three botanical types commonly called races: Antillean, Guatemalan and Mexican.

- The Antillean breed comes from lower areas of the tropics and is therefore adapted to tropical climates and difficult to grow in colder areas.

- The Guatemalan and Mexican breeds come from the highlands of Central America and are therefore adapted to colder conditions.

Varieties that can be grown in temperate zones belong to these two races and are essentially hybrids between the two. However, it must be taken into account that temperatures below 0°C can significantly affect production and, if prolonged, can even kill the tree. For this reason, it is not only necessary to look at the average minimum temperatures, but also at the absolute minimum. Even short periods of time, and not every year, temperatures below -2°C can prevent the cultivation of avocados, although there are differences between varieties.

In the areas of origin of the avocado, rainfall is frequent and the relative humidity is generally high. Therefore, in drier conditions it is necessary to make water contributions that, in the case of southern Spain, we can estimate in about 7000 m3 per hectare and year. The irrigation water must be of good quality, since the avocado is very susceptible to excess salts. As for the soil, ideally it would be enough with a sufficient concentration of organic matter to avoid waterlogging and favour a good growth of the roots, which in the case of this crop, are very superficial.

- The acquisition of plant material is another of the fundamental aspects of cultivation. What should we take into consideration when choosing plants in the nursery?

We must take into account that an avocado plantation is made with a time horizon of at least 20 years, so the choice of plant material is a fundamental criterion for the success of plantations. It is always necessary to resort to reliable nurseries and choose a suitable pattern according to the soil conditions in the plantation area. There are rootstocks with a certain tolerance to salinity or limestone, others with tolerance to Phytophthora cinnamomi and others better adapted to colder conditions.

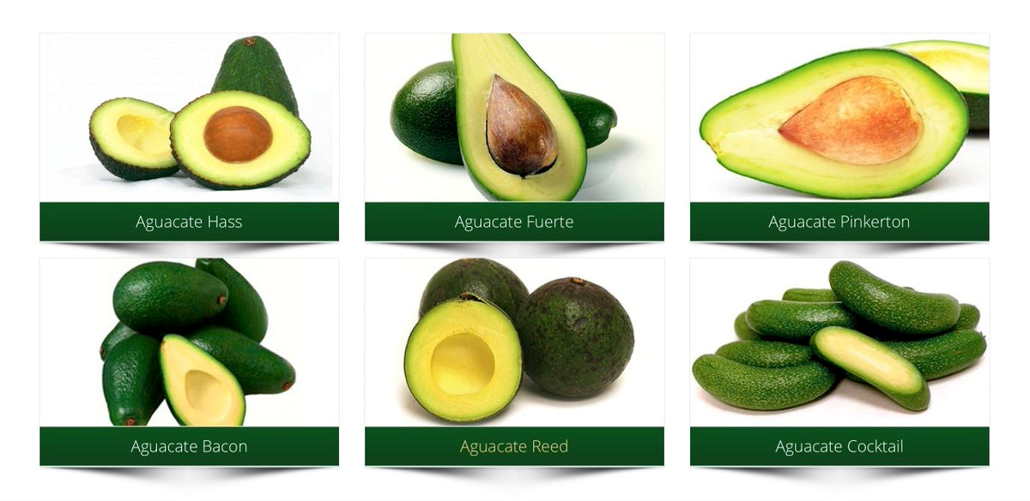

- Hass is the variety par excellence, but are there other alternative varieties with good commercial outlets?

There are hundreds of varieties of avocado. Hass is a variety that emerged by chance in California almost 100 years ago and has established itself as a commercial reference for two fundamental reasons: the change in colour that it indicates when the fruit is ready for consumption (until the 1960s the reference variety was ‘Fuerte’ with a green skin that does not change colour when it ripens) and good post-harvest behaviour. However, in the case of Spain, where in addition to the local market, we supply consumers in the rest of Europe, this second point is not so important because we can reach our destination in a few hours. In fact, with the right combination of some 4 or 5 varieties (e.g. Bacon, Fuerte, Hass, Lamb Hass and Reed) we can have a year-round production of Spanish avocado. And there are many other varieties that can be of interest.

- Making a good choice of varieties for production and pollination is essential but not so easy, because there are pollinators that overlap very well in the flowering of the variety (Flower type A / Flower type B) in some areas of Spain, but not in others. Therefore, it is a theoretical concept that needs some explanation. Can you clarify something about this? What about the percentages and distribution of pollinators?

The avocado is characterized by a very low fruit set (around 0.15% in relation to the initial number of flowers produced). This low fruit set is an adaptation of the avocado in terms of energy consumption. During the evolution by natural selection, plants have been developing strategies to have reproductive success. It is much more economical for the plant to produce millions of flowers with pollen and a few fruits, since avocado fruits require a lot of energy for their development.

However, there is usually an overlap between female closing and male opening flowers (which were female the day before) in the same inflorescence. If we have pollinating insect activity during that overlap there may be pollination within the same inflorescence or between inflorescences of the same variety. The duration of this overlap varies according to environmental conditions and is greater in situations of high relative humidity and temperatures close to 20ºC. Therefore, in many situations most of the fruit set occurs during this overlap. However, planting type B varieties as Hass pollinators can be a safeguard, especially in years of low flower production. From the IHSM we believe that, in most areas of Spain, it would not be necessary to plant more than 5% of pollinators and, in the case of not very large plots, they could be planted only as wind-breaks to a narrow planting frame

- Well, we already know the requirements of soil and climate, the importance of the variety/pattern and pollinators, but before we start planting, what should we take into account to establish the density and framework of planting?

The avocado is a vigorous tree. In some countries, vegetative growth is controlled by means of growth regulators which, however, are not authorised for this crop in Spain. Therefore, in our conditions, the control of the tree size has to be carried out mainly by means of pruning. For this reason, it is difficult to manage commercially at very high planting densities. A 5×4 or 6×4 frame may be the most suitable for most standard/variety combinations.

- Once the crop is established, the really complicated part comes, especially during the first years of planting, starting from soil management to pest and disease control, through irrigation, nutrition and pruning. What is the most recommended soil management for these first years? What alternatives do we have for weed control both in the planting row and in the center of the streets?

We have to start thinking of the arvenous flora as an ally rather than an enemy of the avocado plantation. Arvenous flora fulfills different tasks: it allows improving the soil structure and reducing water evaporation and it is useful to house different species of insects that can act as pollinators and as pest control. However, during the first years of planting, it is advisable to remove this arvenous flora very close to the trunk in order to avoid competition with young plants. This can be done by using a weed control net or padding to prevent the growth of the arvenous flora. After a few years, the shading of the avocado leaves itself makes the plots near the trunk no longer a problem. In the center of the streets, the ideal is to leave the natural flora and proceed to its clearing, leaving the remains in the street itself or around the trunks.

- What type of formation and/or sanitation pruning should we do and what is the most appropriate time to do it?

The seedlings usually come somewhat preformed from the nursery. We must form the trees from the beginning of planting, pruning mainly in spring/summer. The remains of the pruning should be crushed and applied either to the base of the trees or to the streets. In recent years, there are some problems with aerial fungi that cause regressive branch death. If we observe this damage in our trees, it is advisable to eliminate the affected branches and burn the remains instead of adding them to our plantations, since these fungi reproduce by aerial spores and it is convenient to reduce the inoculation pressure.

- Regarding irrigation management, we know that avocado must not lack water, although it does not tolerate excesses either. What would be your recommendation on this matter? Regarding micro-sprinkler and drip irrigation, any advantage/disadvantage that makes us choose one or the other?

Avocado is very sensitive to lack of water but, on the other hand, an excess of water can cause root asphyxiation and favor the development of soil fungi such as Phytophthora cinnamomi or Rosellinia necatrix. Special care should be taken in heavy soils and in that case it may be advisable to use ridge stones to avoid problems, always bearing in mind that they have to be built allowing good drainage of excess rainwater. Both drip and micro-sprinkler irrigation can be used. Perhaps micro-spraying requires more attention from the farmer to review its proper functioning. The important thing is that we do not lose water by percolation and that we take into account that avocado has very superficial roots so it is important that the wet area is as extensive as possible.

- Is avocado an easily mechanized crop?

Soil management if easily mechanized depending on the orography of the terrain. Although in any case, soil management by means of vegetal covers is a positive alternative for avocado cultivation.

Pruning operations on a young plantation must be carried out by hand, and cannot be mechanised. Adult plantations could be partially mechanised, depending on the variety, but they should still be trimmed manually. The more erect varieties would tolerate mechanical pre-pruning better than stunted varieties, mechanisation beyond this is not advisable.

Finally, harvesting is an operation that must be done manually. So far, there are no alternatives to harvest avocado mechanically.

- Soil oxygenation is a positive thing in adult plantations to improve the fruit’s fructification and ripening, but does this practice bring any advantages in new plantations?

The avocado is very demanding in the oxygenation of its roots and appreciates everything aimed at favoring the circulation of air in the soil. In young plantations, it is important to favour the development of the root system and, therefore, measures of soil preparation and crop management aimed at taking care of the soil structure, avoiding waterlogging and favouring the presence of organic compounds that stimulate root growth are fundamental.

- In terms of nutrition, based on a soil analysis and a leaf analysis, what should the crop not miss and when?

In avocado it is important to take care of the supply of both macro and micro nutrients. As for the macros, nitrogen should not be lacking throughout the whole growth period of the tree, which in our conditions takes place from late winter to early autumn.

Furthermore, it has been shown that extra nitrogen applications throughout the autumn indicate positively on production, possibly improving flower quality in spring. Other macros to be considered are calcium, which is particularly important during fruit setting and the first phase of fruit development, and potassium. Phosphorus is also basic, but by experiments conducted in the IHSM La Mayora, we know that in our conditions, there are usually no major deficiencies even without contributions for years, although we must monitor their leaf levels. With regard to micronutrients, special attention to iron, boron, zinc and copper.

- Are inputs of organic amendments recommended?

Organic amendments are highly recommended in avocado not only because of the contribution of nutrients, but also because of their role in preserving soil structure, increasing water retention or stimulating microbial life. In this regard, it is important to note that some organic amendments promote the formation of suppressive soils against fungi that produce root rot in avocado.

- What would be the main pests and diseases to be controlled in avocado seedlings? Do they represent a serious problem for this crop in our country?

In Spain we are lucky to be free of the main pests and diseases affecting avocado in other producing regions, which means that, with good management, organic avocado can be produced. The main pest of the crop is the crystalline mite, which appeared more than 15 years ago in Spain due to the introduction of foreign vegetable material and has already established itself in the whole production area. There are different species of natural enemies (mainly phytoseids) that help to a biological control of the pest. We do not recommend applying acaricides or insecticides since their application eliminates the natural enemies of the crystalline mite and can also affect pollinating insects. This way we can live with the pest that fundamentally has an aesthetic effect on the leaves, since except for extreme situations, it seems that it does not affect significantly the production and neither it causes damages in fruit.

As far as diseases are concerned, the most important ones are the diseases caused by fungi. Aerial fungi of the Botryospharea family that cause regressive death of branches and soil fungi. In the case of Phytophthora cinammomi there are tolerant clonal rootstocks, such as Duke7, Toro Canyon or Dusa. In the case of Rosellinia necatrix, there is a selection program in Spain led by the IFAPA center of Churriana in Malaga, with the participation of the IHSM la Mayora and the IAS of Cordoba. Within this program there are already several advanced selections that we hope to be able to distribute in the coming years at a commercial level. In addition, in some circumstances, there are cases of sunblotch, a disease caused by a viroid. It is important to take extreme precautions in commercial nurseries to avoid distributing plants affected by any of these problems.

- At this point and to finish, where do you think the future of avocado in Spain is going?

Spanish production is less than 10% of European consumption and with the arrival of new players on the market (such as Colombia in recent years or Guatemala and other countries in the near future) this percentage will surely decrease. However, we have a clear opportunity to position ourselves in the most demanding segment of European avocado consumers because, unlike other origins, we produce a highly sustainable product with minimum or no use of phytosanitary products, very efficient management of irrigation water, a low carbon footprint because the transport chain is shorter due to its proximity to our potential market and a much higher quality of fruit, since avocado that arrives in the European market from other origins does so after several weeks of transport by boat. Taking advantage of this opportunity means clearly distinguishing the Spanish avocado as a local product in the rest of Europe and diversifying production, so that we can reach these potential consumers with a combination of varieties that allow us to produce avocados all year round, as opposed to the current situation where we only produce Hass avocados for a few months (increasingly fewer months since there are practically Hass avocados from other origins all year round) and the rest of the year, the large Spanish retailers import Hass avocados from other origins for re-export. In my opinion, if we do not make progress in differentiating ourselves in terms of quality and proximity, it is going to be difficult for the Spanish avocado to be competitive in the medium/long term in the European market.